The extent to which an object resists rotational acceleration about a particular axis is captured by a quantity called Moment of Inertia.

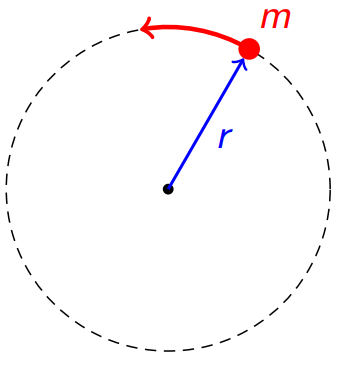

The Moment of Inertia (MOI) of a point mass rotating about an axis at a distance

is

The principle of superposition states that the MOI of a group of point masses is the sum of their individual MOIs. For point masses,

What is the purpose of computing the moment of inertia, and why is it important/relevant in dynamics?

The kinetic energy of a particle in linear motion is

where is the velocity of the particles.

From rotational dynamics, , where

is the angular velocity. So,

This looks like a rotational version of , where

and

. Inertia is the tendency of a body to resist change in its state of motion. So the moment of inertia

is the equivalent of rotational mass/inertia.

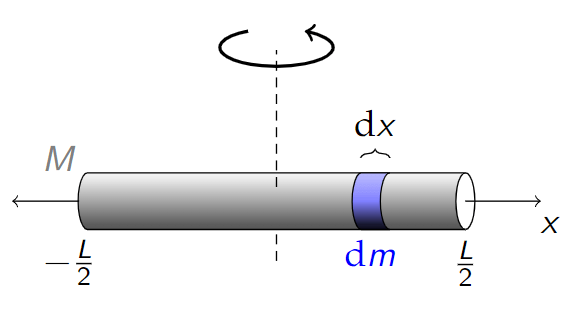

Example – A thin rod (central axis)

We can find the MOI for a thin rod of mass and length

, rotated about a perpendicular axis through its centre of mass.

For a continuous volume , the MOI is given by the integral

where is an elemental mass, and

is the distance from the axis of rotation. Noting that

,

Calculating this integral gives the MOI,

We notice the MOI is proportional to the mass, but also the length squared.

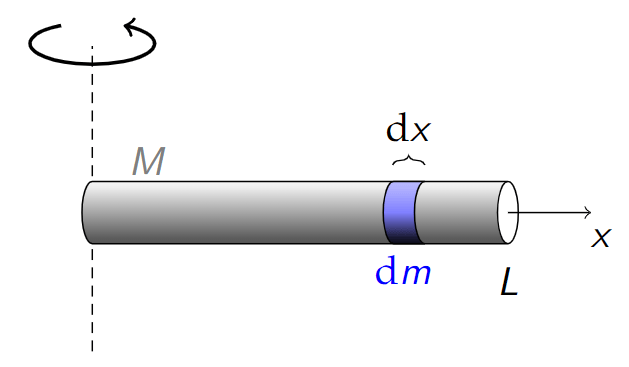

Example – A thin rod (medial axis)

What about finding the MOI for the same thin rod, rotated about a perpendicular axis at one end of the rod?

Now the integral becomes

Calculating this integral gives the MOI,

Note that this result is larger than the previous result. This makes sense given our interpretation of the MOI as rotational inertia. It is easier to turn a rotating door than a standard door of the same mass, since more of the mass is clustered around the axis of rotation.

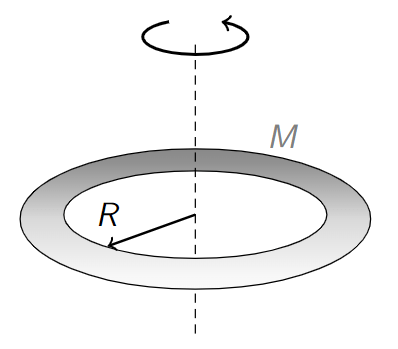

Example – A thin ring

Consider finding the MOI of a thin ring of mass and radius

, about a perpendicular axis through the centre of the ring.

This is easily calculated from the definition,

So

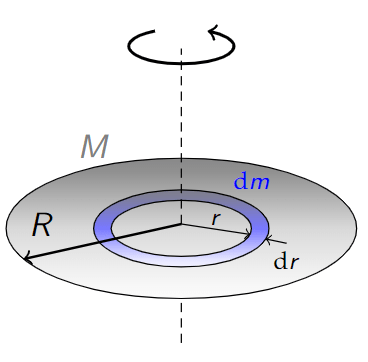

Example – A thin disk

Let’s now find the MOI of a thin disk of mass and radius

.

We first consider an elemental ring of radius and thickness

. The elemental mass

is

Using our previous result, the MOI of the elemental ring is

By summing infinite elemental rings, we can compute the MOI of the whole disk,

The final result is

Note that this is half that of the result for a ring of the same mass and radius.

Check out this short video in which a disk and a ring race down an inclined plane. Which one do you think will win?

The mass of the disk being more uniformly distanced from the axis of rotation means that the disk is has less rotational inertia than the ring, and thus wins the race.

Example – A sphere

Calculating the MOI for spheres takes a little more work, however the results tell the same story. The MOI for a sphere of mass $M$ and radius $R$ is

The MOI for a hollow spherical shell of mass $M$ and radius $R$ is

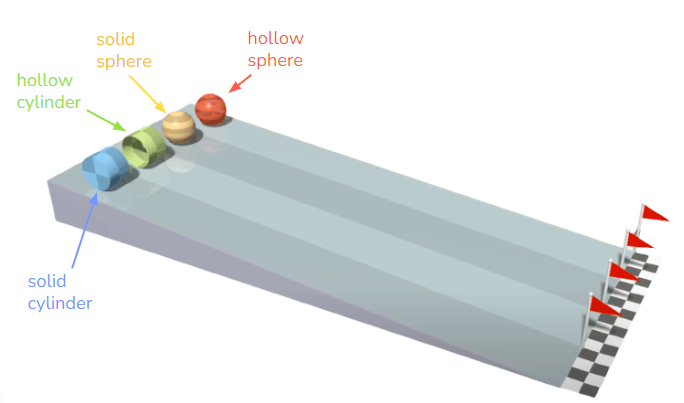

Now consider our race from Part I of this series.

All of these objects have the same mass and radius, and we are effectively asking the question – which of these objects are best at overcoming their rotational inertia, or in other words, which object has the lowest moment of inertia?

Since the masses and radii are the same, all the moments of inertia are of the form

we can simply compare the values of .

Note that since only the cross-sectional area is relevant, we can use the ring example for our hollow cylinder, and the disk example for the solid cylinder. Laying out the results again, from lowest MOI to highest, we see

which explains finally the results of our race.

In the next post we will present some important therorems we can use to find the moment of inertia of more complex, composite objects.

Leave a comment