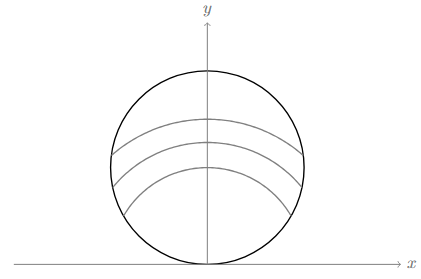

Another great problem I saw on Facebook – picture a unit circle (radius ) centred at

. Which circle centred at the origin has the largest arc-length inside the unit circle?

Consider a unit circle centred at ,

and a generic circle centred at the origin of radius ,

.

Since the first expands to

,

we can subtract this from the second equation and get that . This problem is calling for us to use polar coordinates anyway, so let

and we get that

.

So the two intersection points occur when the angle is and

.

How long is the arclength of this generic circle? Well, arclength on a circle is simply the radius multiplied by the angle swept out by the circular arc, which is , so the arclength is given by

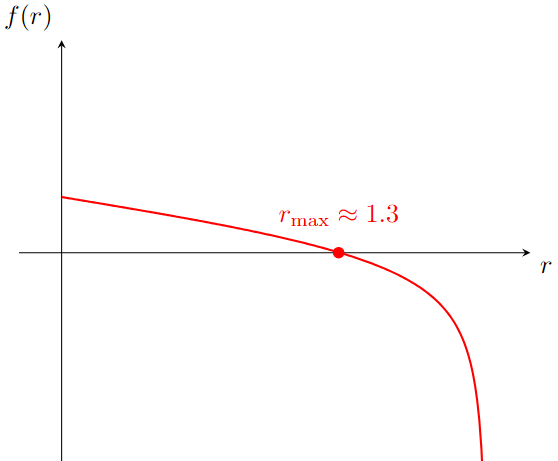

Great! We have the arclength as a function of a single variable, the radius, so it’s time to maximise the arclength with respect to . Differentiating gives

Setting this derivative to zero should give us an equation to solve for the radius of the circle that gives the maximum arc-length,

But there’s a problem! This equation isn’t looking too easy to solve. In fact, it’s impossible to rearrange this equation to isolate . We usually say the equation has no analytic solution.

That doesn’t mean it can’t be solved, though! We’ll have to resort to some sort of numerical approximation, provided for example by wolfram|alpha, which gives us that . You can see a graph of the derivative below. Where it crosses the horizontal axis it is equal to zero, and this crossing point is the radius

.

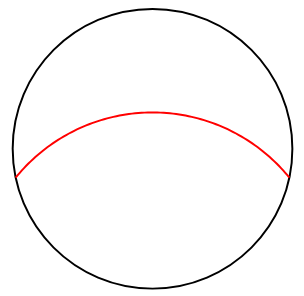

Now we can plug this radius into and find that the maximum arc-length as

. We can also verify this visually in this Desmos example.

So, there it is, the circle with the biggest arc-length inside the other circle.

A nice problem to show to calculus students to demonstrate that not every problem is like the ones in their textbook, with a simple answer expressible in known constants and fundamental operations.

What now?

Well, it turns out that this is one of the rare situations where going up a dimension actually makes the problem easier.

While this isn’t the norm, it happens enough that it’s usually worth keeping in the back of your mind – don’t assume that higher dimensional problems are always harder.

It’s possible that increasing the dimensions involved may teach you something about the original problem.

Tune in for the next post where we’ll be looking at the same problem but with spheres instead of circles!

In the meantime, stay curious.

Leave a comment