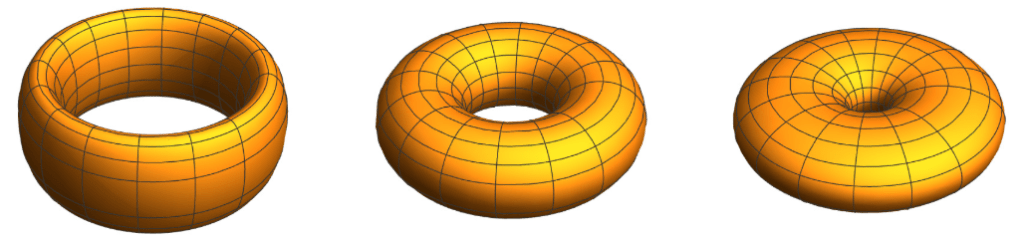

In our previous post we figured out how much of a donut planet had the planet directly overhead. This was done for the regime in which the major radius was larger than the smaller radius

. What about the case when

, called a “spindle” torus?

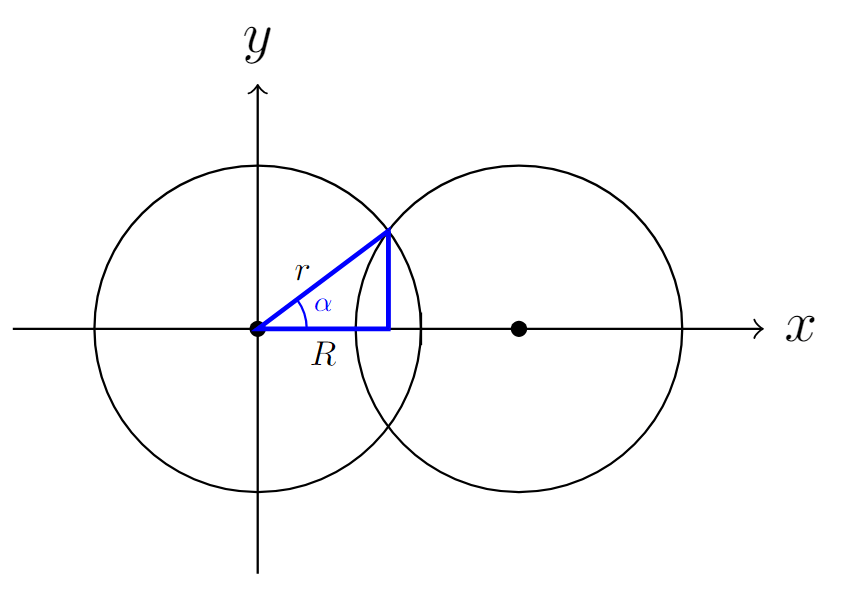

When the circles intersect, they do so at , and we “lose” the arclength inside the intersection from the surface area.

The angle shown for the intersection is . So we lose the angles between

and

, and the arc length becomes

The centroid calculation is pretty difficult, so I’ll spare you the details, but the horizontal coordinate is

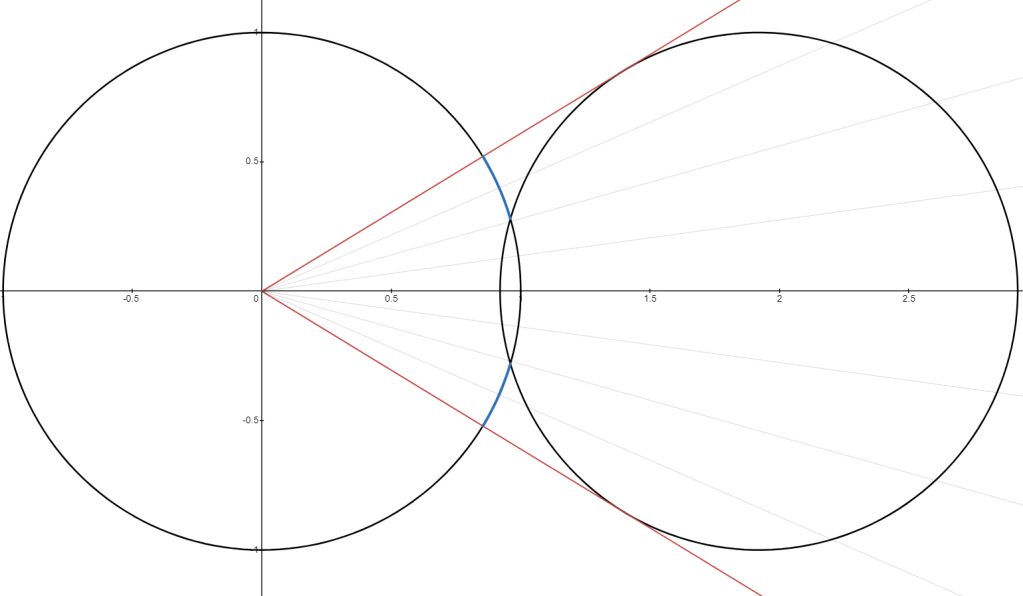

Note that as decreases, we reach a point where the circles are orthogonal (their tangents at the point of intersection are perpendicular), and there is no longer any point on the surface that can see the other side.

The circles are orthogonal when the angle is 45 degrees, or when .

Below this point, then, the percentage is zero!

So we finally have the piecewise function that defines the percentage of the Earth that can see the other side.

Overall I think this would make a great question for a high school or pre-calculus class in university to discuss, or maybe do on an assignment. It’s a good introduction to why piecewise functions might arise naturally in considering problems that hide some complexity.

As usual, answering this question brings up more questions. Like, could we repeat these calculations for an elliptic torus?

What would it actually be like to live on a toroidal planet? Would the gravity be significantly different on the inside compared to the outside? Given that you’re attracted both to the side you’re standing on, but also to the side opposite you, and everything in-between. It’s sort of like a continuous version of the 3-body problem.

Would satellite orbits be stable? One might imagine that far away from the torus, the gravitational attraction from the planet would be similar to a sphere, so long range elliptic orbits should be possible. But what about figure-8 style orbits through the central “hole” of the donut?

What would the day/night cycle look like? Tides? The magnetic field? Could the atmosphere cover the hole in the middle if it was small enough? Could we have lifeforms floating in the middle of the torus where gravity is negligible, taking advantage of weather patterns unknown to a spherical world?

I found this blog post which is a fun read if you’re interested in thinking about these questions further.

Leave a comment