This is a bit of a departure from the usual content of this blog, more a musing on an odd bit of trivia regarding mathematical history, nation building, and an iconic landmark at the heart of one of the world’s most famous cities.

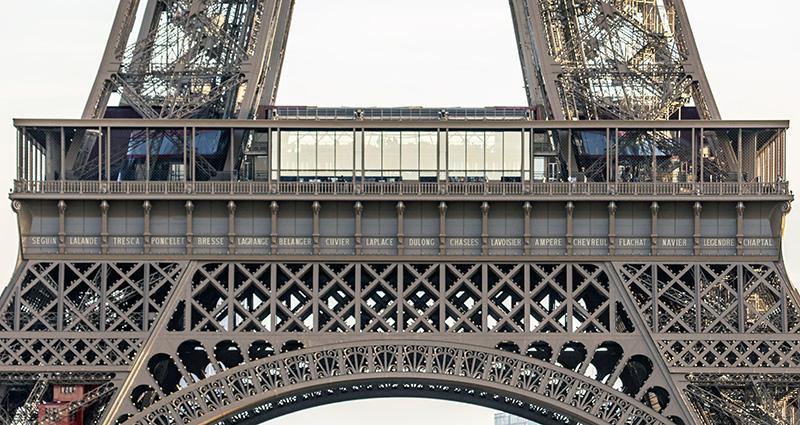

Named after Gustave Eiffel – his company completed the tower in 1889 as the centre-piece of the world fair that year, the Eiffel Tower bears seventy-two names, engraved just below the first platform: mathematicians, physicists, engineers. The official story is tidy and reassuring. These are “the seventy-two great French scientists of the last hundred years.”

There are many prominent names on the list, familiar to any student of mathematics: Lagrange, Laplace, Cauchy, Poisson, Fourier, Legendre and d’Alembert among them. There is a strong bent towards analysis, mechanics and geoemtry, mathematics that directly underwrites engineering and physical law.

The absence of figures such as Darcy, Galois, Liouville, and Hermite is not accidental; their work did not align with the tower’s industrial–mechanical narrative. Fourteen of the names belong to hydraulic engineers, for instance, as water control mattered to industry, sanitation, and empire.

The first and most obvious lie is one of omission – the tower does not feature the name of a single woman, not even Sophie Germain, noted French mathematician whose exclusion is made even more ridiculous by the fact that her work on the theory of elasticity was used in the construction of the tower itself. Scientist and explorer John Augustine Zahm conjectured as far back as 1913 that her lack of acknowledgement was simply because she was a woman.

Germain was a major contributer to number theory. She has a type of prime named after her. She also proved a crucial partial result toward Fermat’s Last Theorem, proving the result for all primes under 100. This was the first major theoretical advance on Fermat’s Last Theorem since Fermat himself and remained unsurpassed for decades. It introduced techniques later absorbed into algebraic number theory.

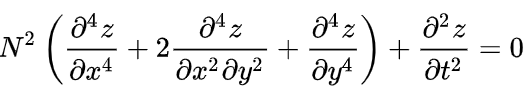

She also devloped the theory of elasticity and even discovered/invented the concept of mean curvature, which I am going to start calling Germain curvature. This is a measure of the curvature of a surface, and is the average of the curvatures in two perpendicular directions. It is an important quantity because it is conserved across different points of the surface, and tells you a lot about its nature.

She made the first serious mathematical attempt to derive the differential equation governing the vibration of elastic plates. For this work she won the Grand Prix of the Paris Academy of Sciences (1816), the first woman to do so. Even after winning the prize, however, she was unable to attend lectures at the academy (women were banned, unless they were a wife of one of the members). This matter was rectified with help from Joseph Fourier, but it took seven years.

Germain also features in one of my favourite stories about Carl Freidrich Gauss, one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, and one of the only German mathematicians of the late nineteenth century comparable with the French elite. Sophie had been corresponding with Gauss under a psuedonym of M. Le Blanc. When she finally revealed her true identity, Gauss wrote to her, saying

“How can I describe my astonishment and admiration on seeing my esteemed correspondent M. Le Blanc metamorphosed into this celebrated person … when a woman, because of her sex, our customs and prejudices, encounters infinitely more obstacles than men in familiarising herself with [number theory’s] knotty problems, yet overcomes these fetters and penetrates that which is most hidden, she doubtless has the noblest courage, extraordinary talent, and superior genius.“

Emphasis mine. I will always think highly of Gauss for this.

The other lie is one slightly more suprising than the misogyny of nineteenth century European society—not least because it is quite difficult to verify using standard search engines.

The lie is that all 72 men listed on the tower are French.

There are at least two notable examples. I remember my suprise at learning that one of my favourite French mathematicians, Joseph Louis Lagrange, responsible for large contributions to the calculus of variations, foundational results in celestial mechanics and important results in algebra, number theory and probability – was actually Italian.

Lagrange was born in Turin in 1736, then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia. His name at birth was Giuseppe Luigi Lagrangia. Though he had a French grandfather, his education, early career, and mathematical style were shaped in Italian intellectual circles. He did not grow up French, was not culturally French, and did not initially write in French.

He later moved to Berlin, then to Paris, where he spent his final decades. He became a French citizen late in life, during the Revolution — at a time when France was actively absorbing eminent European thinkers as symbols of universal reason. At best we can say he was naturalised as French.

The second example is Charles-François Sturm, best known for Sturm’s theorem and for co-developing Sturm–Liouville theory with Joseph Liouville. His work on the theory of equations and differential equations deeply influenced 19th-century mathematical analysis and mathematical physics.

As far as I can tell, Sturm is at most half French. He was born in Geneva to a father from Strausborg, which, while lying on the border of France and Germany (Sturm is a name with clear Germany influence) does belong to the French side. His mother is more difficult to find information on, however she does appear to be Swiss. He did move to Paris later in life, however his early work was published in Italian.

Now I understand that this incredibly pedantic “fact” isn’t interesting to everyone, however it is interesting (to me at least) that it is essentially un-googleable. In fact, its a nice example of the case for LLMs as a search tool, although it appears to be right on the edge for them too – some of them will happily state that all 72 names are French, while other more advanced incarnations give the more nuanced explanation.

Evidently, the names on Eiffel’s tower were chosen to present France as the intellectual engine of modern science, a nation whose progress flowed naturally from the rationality of the Enlightment to the triumphs of the industial age. In claiming a few half or quarter French geniuses as examples, the tower seeks to create a narrative about nation building and imperial might.

Okay, so clearly we have to leave Lagrange. What about Sturm? I am not impuning his work, which is foundational and which I have good memories of learning in my PDEs class at university. I merely question his ‘Frenchness’. Can we take his name down and replace it with Sophie Germain’s?

Happily, it seems as though we don’t have to.

Just last year, Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo commissioned experts to undertake the project of listing 72 female scientists to adorn the tower, a proposal that was reviewed by various academies of science, technology and medicine.

Just days ago, it was confirmed that Sophie Germain’s name will feature alongside those of Marie Curie and Rosalind Franklin, inscribed for all to see on one of the world’s most famous structures. See the full list of names here.

I, for one, hope to make another trip to Paris soon, to see the new and improved Eiffel tower.

Leave a comment