In Part II of this series, we wondered whether the result of the area being constant continued into higher dimensions, but, assuming it does, we also wondered whether there was any logic to the sequence of the actual value of these constant volumes.

A reminder that we currently have

This bugged me for a little while, and then I remembered something I learned a long time ago regarding the volume of a 4D sphere. For that we need a short aside.

The volume of an n-ball

Technically, mathematicians like to call the outer shell of a spherical object a sphere, and the entire thing a ball. A 3-ball for instance, would be a regular dense ball you would use in a game of snooker.

A 2-ball would be what most people call a circle, but mathematicians actually call a disk (the circle being the perimeter of a disk). If you remember your high school maths class, the formula for a circle of radius is

and the disk is everything inside,

What’s the formula for all the points in the solid 3-ball? There is one more dimension, so we need another variable ,

The volume of a sphere is given by

.

What’s the volume of a 4-ball? What the heck is a 4-ball, you ask? And why would I know its volume?

Good question. You probably wouldn’t, unless you calculated it or read this Wikipedia article, because 4-balls simply don’t exist in our universe. I can’t show you a picture of one either, but I can tell you the formula because its just extending the previous formula by one more variable,

And the volume?

See where I’m going with this?

These values look very much like the ones we’re getting in our paraboloid problem. Let and they’re almost identical,

| Paraboloid volumes | |||

| Volume of balls |

apart from a factor of .

The volume of a unit ball in dimensions, as per the wiki-article, is

I’m not going to cover the Gamma function here, but since we have this formula, we can compute all the values for the second row of the table, and thus we have a conjecture for the paraboloid tangent volumes we’re looking for, namely that it’s the volume of a ball of two dimensions higher, divided by .

As yet another aside, the volume of a unit ball in higher dimensions actually peaks in 5-dimensions (see the red dots in the graph below).

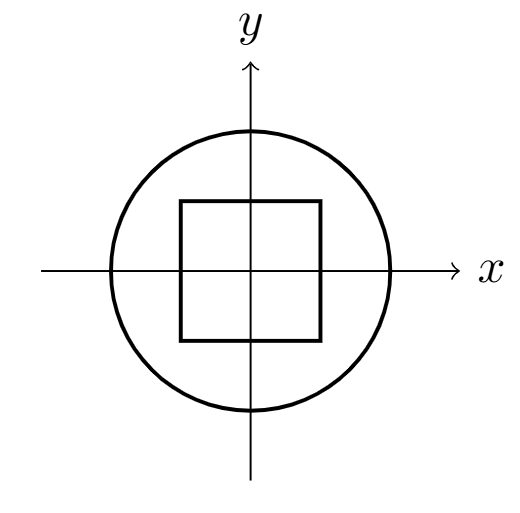

Weirdly, the volume goes to zero as , while a hypercube that spans from -0.5 to 0.5 in every variable will always have hypervolume of 1, meaning that at some point the unit hypercube must “poke out” and escape the unit sphere, sort of like what does very much not happen in two dimensions.

This is a great example of our lower dimensional intuition failing us. In fact, the -dimensional unit cube is completely inside the

–dimensional unit ball only for

. I just find this really weird and interesting.

Back to our hunch.

Now that we had this direction, we knew what should come out of the calculations. David was able to prove, using hyper-spherical coordinate transformations, that the hypervolume bounded by the tangent hyperplane and the hyper-paraboloid is

The way this was done was pretty technical, involving some pretty cool Beta function identities and products over the Gamma function, eventually I’ll update this post with a link to the derivation for those who are interested.

If we take the -ball formula and replace

with

, we get

Using the defining property of the Gamma function that , we can reduce this to

and finally, making the link with from above,

which is what we wanted to prove.

So we have a very strange relationship between two seemingly unrelated problems. We have no real intuition for why this is the case, or if it’s even very meaningful to compare say, an area from one problem to the volume from another.

As far as we can tell, the iterated integrals used to calculate these volumes simply turn out to be similar.

There’s a lot more we could (and did) try with this problem, including asking ourselves the question “Are parabolas the only function where this is true?”

One could imagine a more arbitrary function with some restrictions (differentiable, monotonic, perhaps even), and its copy shifted up by one unit. If we found a similar area bounded by the tangent and the curve below, would it be constant for any other classes of function? I thought I might be able to reduce this problem down to a functional equation where the only solution would be a general quadratic, but have had no luck so far.

If this is all blindingly obvious to you, please reach out and let us know what we’re missing, and maybe this journey will continue.

Otherwise, I hope you enjoyed this series, and we’ll see you in the near future with some more interesting problems.

Stay curious.

Leave a reply to A problem of paraboloids – The Calculus of Explanations Cancel reply