Last time we saw that the problem of finding the circle with the longest arc-length wasn’t possible analytically, and we had to resort to numerical or graphical methods.

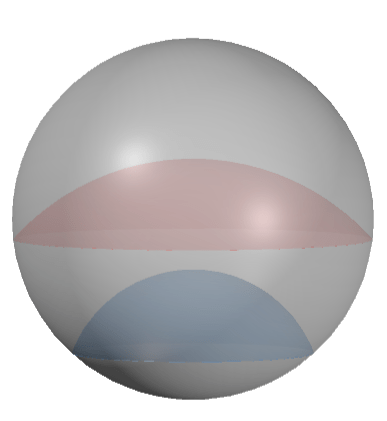

Now we extend the problem to find the sphere centered at the origin with the largest surface area inside a unit sphere shifted vertically by one unit.

Here we define a sphere () centered at

:

And the ‘expanding’ sphere () centered at the origin with radius

:

Where . Here we seek to solve for

that optimises the surface area of the intersection of

and

. We first solve for the intersection of

and

:

Setting the right hand sides equal gives us that for the points at which the two spheres intersect.

To identify the region this corresponds to in and

we substitute

into either

or

. Here, we choose

for simplicity:

Here we observe that and

intersect at

over a circle centered at the origin with radius

. Call this region

.

We first observe that the radius of the expanding sphere is . From there, we can define the surface area

of

over

as the double integral:

Recall for that

Similarly, we have . Thus, we have:

This integral is crying out for a substitution, into the polar coordinates given by and

. Under this transformation the integral becomes

A remarkably simple formula for the surface area of the expanding sphere!

To find the one with the maximum surface area, we take the derivative and set it equal to zero,

This equation has two solutions; (clearly a minimum), and

, which is the radius of the sphere with maximum surface area. If you like, show the second derivative is negative to prove this is a local maximum!

If we put this value back into our surface area formula we get that the maximum area is

As we mentioned in the previous post, this seems to be a problem that (in some sense) becomes easier in one higher dimension.

However you feel about double integrals aside, it is interesting that in the case of the circles, the equation to solve for the optimal radius was analytically intractable, whereas for spheres, it is a simple quadratic.

This allows us to achieve a closed form solution for the maximum area in 3d, something that wasn’t possible in 2d.

Actually, we think that dimensions is the only time this happens, and in all other

it becomes necessary to solve

numerically.

Interestingly, this seems to be true for different reasons depending on whether the dimension is odd or even.

But that’s a story for next time.

Stay curious.

Leave a comment